This is a very meaningful interview for us, and we are confident the reader will appreciate the effort behind it. You see, Dead Feather is a project unlike any other. A deaf multi-disciplinary artist, the American creative is mostly active within the visual and aural mediums, packing his work with a keen community-driven ethos. Honouring his roots, the talented visionary focuses on the subject of assimilation and the civilisation process concerning the North American Indians, in particular the MvskokeCreek.

Recently, Dead Feather has unveiled a striking piece of music, ‘American Dreams’, a potent song that looks at the relations behind the U.S.A. as we know it and its relationship with Indigenous people. Framed into a gloomy and epic blues-rock livery, ‘American Dreams’ is taken from the overarching album ‘Cate Heleswv (Red Medicine) Vol. 1’, out now.

Intrigued by the project, we caught up with Dead Feather to find out more about his peculiar, researched artistic vision and any future goals. Interview below.

Hello Dead Feather, it’s a pleasure to chat with you. Reading through your history and artistic ethos, it is clear that your overall work is incredibly meaningful and partly challenging, too. There’s a lot to cover, so let’s move through specific questions, aiming to educate listeners about you and your project. First of all, I’d love to know more about the Mvskoke-Creek community and your overall upbringing; when did you first realise that there was a special bond between you and your historical roots?

Hello! Thank you for your interest and time. And what a great question. I don’t know if I ever realised there was a special bond, but I do know I was always treated differently, no matter where I was in life, from growing up to adulthood. It still continues to this day. When these types of challenges come up, I can always connect with my ancestors spiritually by reading and researching and somehow expressing that isolation and frustration creatively.

Growing up with my grandfather, I observed that his father and all of his relatives before him spoke Mvskoke-Creek and practised their traditional customs in one way or another. He was sent to a boarding school and forced to speak English using the Bible as a main source of learning. Much like the same process used to civilise the Mvskoke-Creek under George Washington in the late 1790s.

He eventually became a Baptist preacher. It was interesting to see and listen to him talk about Creek history and mythology with our distant cousins and relatives, but then back in the household, none of the Creek language or stories were even mentioned or spoken of. “It’s a White Man’s World” is what his father would tell him. It wasn’t until he was older that he began to encourage his children and grandchildren to learn the Mvskoke language and history.

As a child, I remember observing my surroundings and realising I didn’t connect with the Church or its practices or beliefs. I remember being spiritually confused and trying to understand why my family was following these rituals and practices that had nothing to do with the customs and stories of my distant Mvskoke-Creek cousins and relatives who grew up under a more traditional household. I suppose the “bond” came later in life, after years of creating various mediums of art that centre around Mvskoke-Creek and Native American themes. My work is more of an educational tool for myself. Should the viewer be educated and entertained by my work as well, I sincerely appreciate interest.

Art has now become your preferred outlet of personal expression, even in the face of deafness and societal inequality. Let’s take your paintings, for instance. What are some common images or themes you find yourself painting over and over?

The artwork has definitely become a vehicle for my frustration and confusion, especially the paintings. As with any artist or creative type, the work develops in stages. As for the painting portion of the Dead Feather concept, it started as collage work. My interest in media and its historical use in government psy-op programs, which aimed to influence political thought and agendas, sparked the painting journey. The ways these operations unfold are essentially the same way those operations that set the civilisation process into place unfold, only it’s on a grander scale these days. This is beyond native and non-native.

Eventually, the process extended to oil pastel finger paintings, which make up the majority of my painting work. These paintings began after gallery curator and art collector Dan Brackett (now deceased), who was running the Jacobson House (Home of the Kiowa Five), began to reach out to me for more artwork. In order to prove to him I could actually paint, I did a series of 25-30 oil pastel pieces derived from photos taken by Edward S. Curtis (the Shadow Catcher). This was essential in branching out my education and research into Native American history. The process from the collage days carried over onto these pieces.

You may notice a lot of lines, angles and circles or bits and pieces of words and letters placed throughout. This was meant to represent my hearing loss and the vibration of sound. It’s also a reference to the unseen. Being guided by forces beyond your control. You may also notice the corners have a heavy overflow or drip. This was meant to represent the loss of resources through the land and the loss of traditional beliefs, culture and practices due to relocation and the civilisation process of the North American Indian.

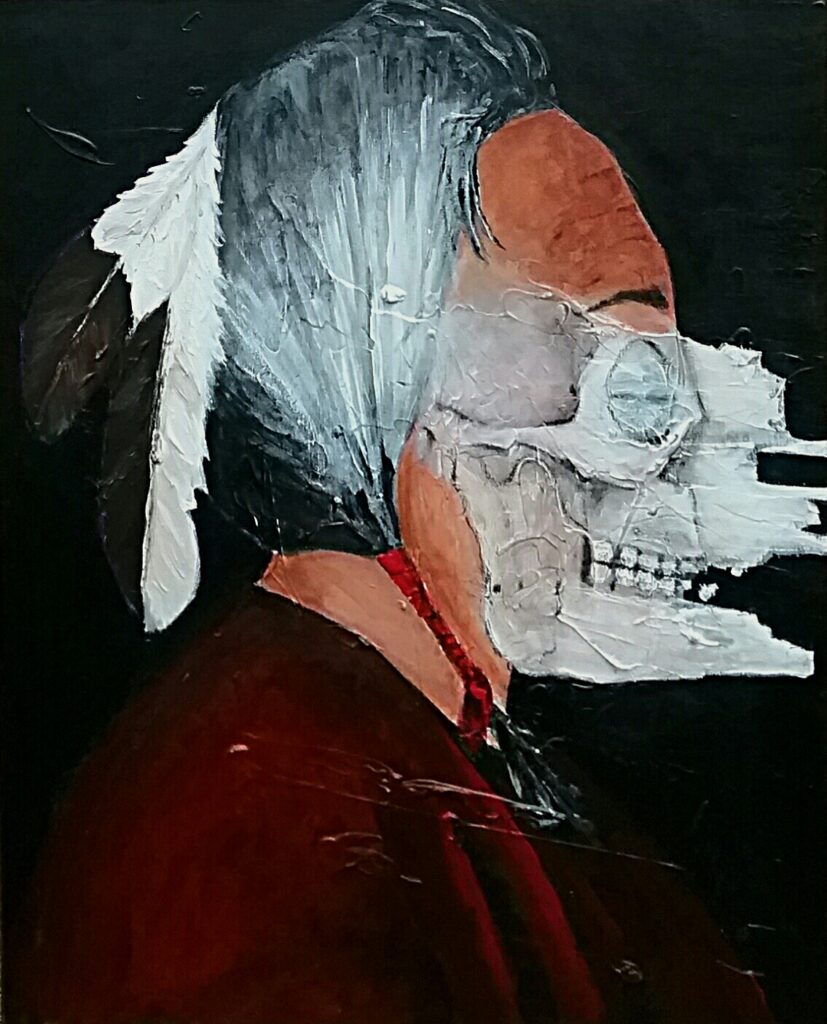

Eventually, the paintings shifted to acrylics. In this series, you will find a lot of religious imagery and figures in which I incorporate various animal skulls, representative of trickery in Mvskoke-Creek and indigenous folklore over their faces. This was a way of dealing with my cultural isolation and conflicted spirituality, I suppose. The main figures are Saint Sebastian or Onuphrius. Onuphrius was a favourite of mine to paint. I relate to the story of the loner who went off to the mountains to listen for the voice of God. But those are the main repetitive themes in the paintings I do. I haven’t painted since 2020. I may paint again in the future, but I’m in no rush.

Besides paintings and music, do you enjoy other art media?

Well, music is the latest attempt at a creative project. Since I’ve decided to start a creative journey in the late 2000s, I’ve attempted many forms of creative expression. I believe it started with poetry. Actually, one of the songs on the new album Cate Heleswv (Red Medicine) Vol.1 is a poem I wrote from that era. I want to say around 2008. It’s called Red Poem. I had just met Dan Brackett as he was working with another Native American artist. This is around the time he asked me for more paintings, and the painting journey began.

In between painting, I would attempt to make small dolls, which I called the Este Lobutke (Little People). In Mvskoke-Creek folklore, the Este Lobutke would guide the heleshyv (medicine man) to the local plants and herbs to heal and help the community. I took that element and attached a small booklet to the dolls, which were intended to be similar to something a small child would play with during the forced relocation, and added a small conversation in Creek, along with the numbers one through ten and various animals in Mvskoke-Creek. I show how the words look and how they’re pronounced in the Mvskoke tongue.

The idea was to use the dolls as the Este Lobutke would act, to guide the observer to the world and language of the Mvskoke-Creek. Along the way, I was getting into Native American history, not just Mvskoke-Creek history. This is where I began making masks to put together a play expanding on the stories of various Mvskoke-Creek deities and monsters that have been lost due to the civilisation process.

Being so far removed from my culture, I have to borrow from other tribes to learn about my own culture. For the masks, I borrowed heavily from the Southwestern tribes. The Mvskoke didn’t have masks in the same sense as the Southwestern tribes did. The idea was, if I make these masks, I’ll have a visual representation of all these various Mvskoke-Creek deities and monsters. It makes it easier to remember, plus they look really cool and fit the Dead Feather aesthetic. Of course, there are other means of expression, but those seem to be the main elements of the Dead Feather concept. The Dead Feather concept is constantly growing. It’s definitely a lifestyle.

‘American Dreams’ is your latest aural effort, a stunningly guitar-powered cut drenched in meaningful lyricism and nostalgic rock flair. It’s taken from a larger body of work, defined by you as an ‘audio sculpture’: “Cate Heleswv (Red Medicine) Vol. 1”. Why are you using such a powerful definition, and what can we expect from the upcoming album?

I didn’t realise I was using such a powerful definition. You’ll have to excuse me. But, yes. Cate Heleswv (Red Medicine) Vol 1. is part one of a series of four planned albums. Album one is an introduction to the Dead Feather world. The other three expand on Mvskoke-Creek spirituality, history and monsters. But back to your phrase “powerful definition”. I suppose the phrase seems powerful because I’m approaching the album and music project as a sculpture. Not so much as an album in the traditional sense.

The album is intended to be listened to while viewing the Dead Feather concept in its gallery setting. The album is just an extended canvas for the Dead Feather concept. I currently have 100 vinyl pressings of the album on the way. Being a vinyl collector in the past, I always wanted to incorporate vinyl into the Dead Feather concept. This project allows me to accomplish that goal.

‘American Dreams’ was written by you with the aid of Adam Stanley and Isaac Nelson. Delving deeper into your songwriting, do you spend a lot of time conceptualising lyrics? How do you approach the production phase?

Well, during the last four years, I completely shut down creatively after trying to get the Oklahoma art community to sponsor, fund or help with getting a play done in which I expand on the stories of various Mvskoke-Creek deities and monsters. One would think the state of Oklahoma would hop on board with an artist educating the state about Native American history, especially about a tribe that was forced to relocate to this state, as well as having its headquarters based in this state.

But that’s not necessarily the case. The generally accepted image of what Native American art looks like is centred around traditional styles. However, many Native artists of the past have applied a pop culture element that style, giving it a mass appeal charm. I suppose my work goes in the opposite direction, and I can see how that can be off-putting to the casual observer of Native American-themed art.

There’s a real heavy gatekeeper mindset that permeates Oklahoma and its art community. So for a while, I delved into short films and collaborated with Atlanta-based film-maker and documentarian Wilson Stiner. We made a short documentary titled Ehute-vpohyvke (Home-sick). During that downtime, I forced myself to learn chords on my acoustic guitar, then started studying basic song structures. The lyrics were mostly already there, swimming around in my head. Being familiar with wordplay and poetry, the lyrics kind of just came out on their own. I just focused on a subject matter and let the pen do the walking. Once I figured out how to make song structures, I pieced the lyrics together with the newly written songs and called it an album.

The production process was a whole different experience. In my mind, I was just envisioning an acoustic guitar and my voice. But after talking with Adam Stanley and Issac Nelson of Stanley Hotel, a whole new world came to mind. They took my campfire songs and turned them into this huge production, which was exciting to me because I always wanted to make a rock n roll record. Basically, they would record me and the guitar as a blueprint. Then they would gradually add the instruments and begin layering the song.

Adam and Issac were the ears to the whole project. Without their talent and dedication, the Dead Feather sound would not have happened. They added their elements and flair that I wasn’t sure of at first, but after watching it unfold, I was just completely amazed. It’s what I was going for as far as a good rock record. Of course, I’m probably hearing something completely different from the average listener, but the vibration I get when the album plays is pretty rock’n’roll to me.

With Elizabeth Swindell’s horn work and the background vocals of Elexa Dawson, Carli Dawson, Rose Dawson and Cameron, watching them go to work in the studio was like watching magick come to life. There was this part on Corn Woman (Mother Woman) where we were using their voices individually, like a painting. As we were recording the breakdown, the way their voices were structured resembled a spiral. If you listen closely, maybe you’ll hear what I’m talking about. There was definitely a heavy spiritual pull during the recording process. But like I said earlier, watching the production come to life was pure magic.

I am truly intrigued by the way you are able to be so active in music despite the many challenges you had to face. In particular, I’d be interested in knowing how you generally experience music: through scores, lyrics? And if you have any reaction at all to aural inputs?

To help you better understand how I “hear”, I fell off a slide when I was an infant. It damaged my hearing. So, I can hear sound, but not high pitches or quiet sounds. And what I do hear is probably not the pitch a normal person would hear. Also, everything is just sound. Mumbles. Noise. I read lips. I familiarise myself with the everyday sounds of human communication and experience. People often ask why I don’t wear hearing aids. It’s just amplified noise. Technology can’t fix everything.

Now to answer your question as to how I experience music, I suppose like anyone else. If the vibration of the song makes me feel good, the artist has a good visual aesthetic, and the lyrics have some sort of intellectual value, I’ll probably enjoy it. It’s funny that you mention scores. There are certain movie scores I love and certain classical artists I adore, when I can hear them. Unfortunately, I can’t hear the high notes on stringed instruments like the violin, and that can get annoying sometimes because I want to hear the rest of the song because I’m riding high on these emotions then it just stops until I can hear it again.

I have to REALLY listen. I mean this in a light-hearted way. Also, stringed instruments seem interesting to me because I’m attracted to the various tales that involve deals with the Devil or some other ominous being in exchange for some great talent or gift. That’s so rock’n’roll to me.

Circling back to your Native American roots, are there any collective efforts to keep the Mvskoke-Creek culture and community alive? Are you in touch with other members of the community?

I recently did a short documentary with Atlanta-based documentarian Wilson Stiner called Ehute-vpohyvke (Home-sick). It introduces my work and explores my desire to visit one of the mounds in Georgia. The Mvskoke are descendants of the Moundbuilder culture. I’ve never been to those mounds, hence the title Home-sick. Wilson won Best New Director for Ehute-vpohyvke during the Bare Bones Film Festival a couple of years ago. We’ve been trying to connect with the Mvskoke Nation in Georgia to help with his project that is also based on Mvskoke-Creek themes.

That’s about the extent of our communication with the Creek community in Georgia. As far as Oklahoma, there has been no exchange of information between the Mvskoke-Creek community and me. As for my art, I don’t think that anyone raised in a traditional native household or had a traditional native upbringing would need this information. It doesn’t apply to their life or lifestyle. They already know about the subject at hand.

For me, the Dead Feather concept is a spiritual journey for myself. If I need to reference something, I can simply look at a painting or whatever and attach something historical or educational to that piece. It’s a learning tool. But it’s also about being the best you can be in any given situation. How will you make your environment thrive? What are you putting in your diet, both mentally and physically? What do you surround yourself with? Are your actions helping or harming the planet? It’s a daily ritual of sorts.

You know, when the original Mvskoke arrived in the New World on a turtle’s back and Hesaketvmesse cleared the fog, we emerged from the fog and began naming our clans after the first things we saw. The Wind Clan was the first to be named. That’s what Dead Feather represents. The death and eradication of any cultural or traditional practices due to the civilisation process. Looking back at my family history, I’m a distant cousin to Citto Harjo, the leader of the Snake Uprising. And if we were to go by clan, I am connected to the great native prophet Tecumseh. I think people misunderstand the Dead Feather concept at times. But, I digress. Hopefully, the doors of communication between the Native community will open soon.

What are the next steps for Dead Feather? Anything exciting on the horizon? Also, if one wanted to buy/admire your visual art, how would they go about it?

I’m currently sharing the album with anyone who wants to listen. Should the next three unfold, we’ll see what happens. In the meantime, I’m just practising guitar, creating when the need arises and riding this music wave. It’s all pretty exciting.

I generally never sell my work at my art shows. I have sold some for the right price. But I suppose if you were a serious art collector, you could email me at deadfeathermvskoke [at] gmail .com // Visit my website for more information on the Dead Feather concept.